Digestion is a cornerstone of health, and within the digestive system, each organ plays a pivotal role. Among these, the large intestine is frequently overlooked in favor of flashier digestive components like the stomach or small intestine. However, understanding what is the primary function of the large intestine can radically transform one’s approach to gut health. Far from being a passive passageway for waste, the large intestine actively shapes the final stages of digestion, influences the microbiome, and contributes significantly to immune regulation and overall well-being.

You may also like: Essential Steps on How to Rebuild Gut Microbiome for Better Digestive Health

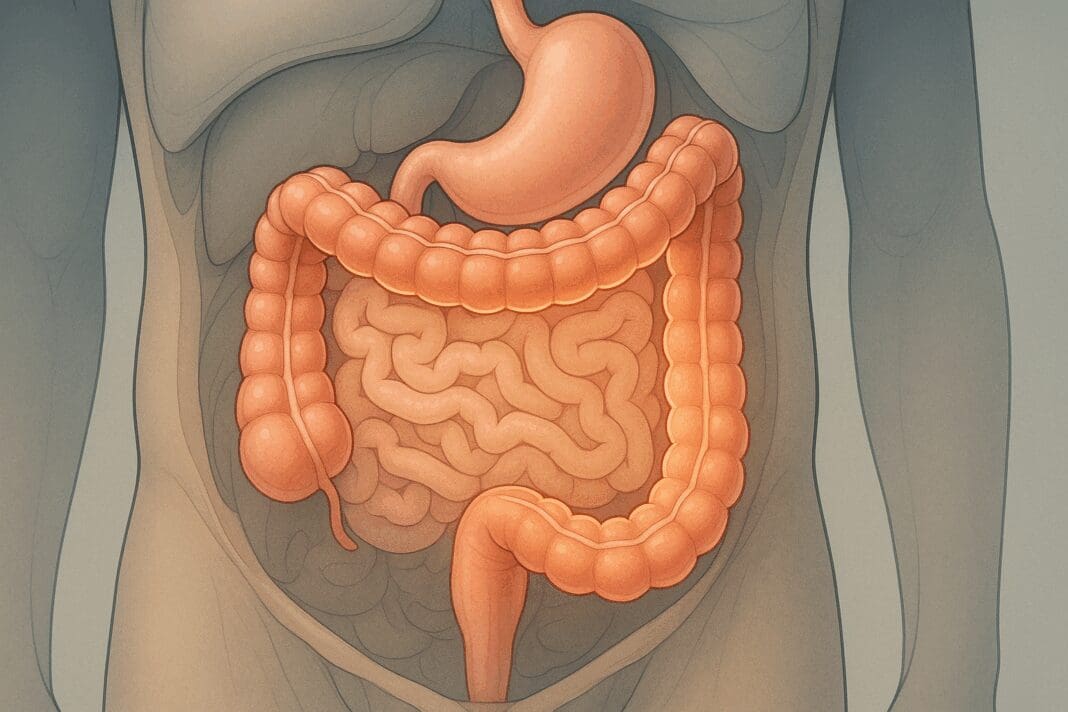

Demystifying the Large Intestine: Structure and Significance

Before we dive into the nuanced functions of the large intestine, it’s essential to understand its anatomy. Often referred to colloquially as the colon gut, the large intestine is a muscular tube measuring about five feet in length and two and a half inches in diameter. It begins at the cecum, extends through the ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoid colon, and concludes at the rectum and anus. This progression of segments reveals the structural complexity and coordinated functionality of the large intestine, which is crucial for maintaining homeostasis.

The large intestine differs notably from the small intestine in both structure and function. Unlike the small intestine, which specializes in nutrient absorption, the large intestine focuses on water reabsorption, electrolyte balance, and the consolidation of fecal matter. The components of the large intestine work in harmony to extract value from waste and prepare it for excretion, a role that highlights its quiet but vital contributions to digestive efficiency and overall health.

What Is the Primary Function of the Large Intestine? A Deeper Look

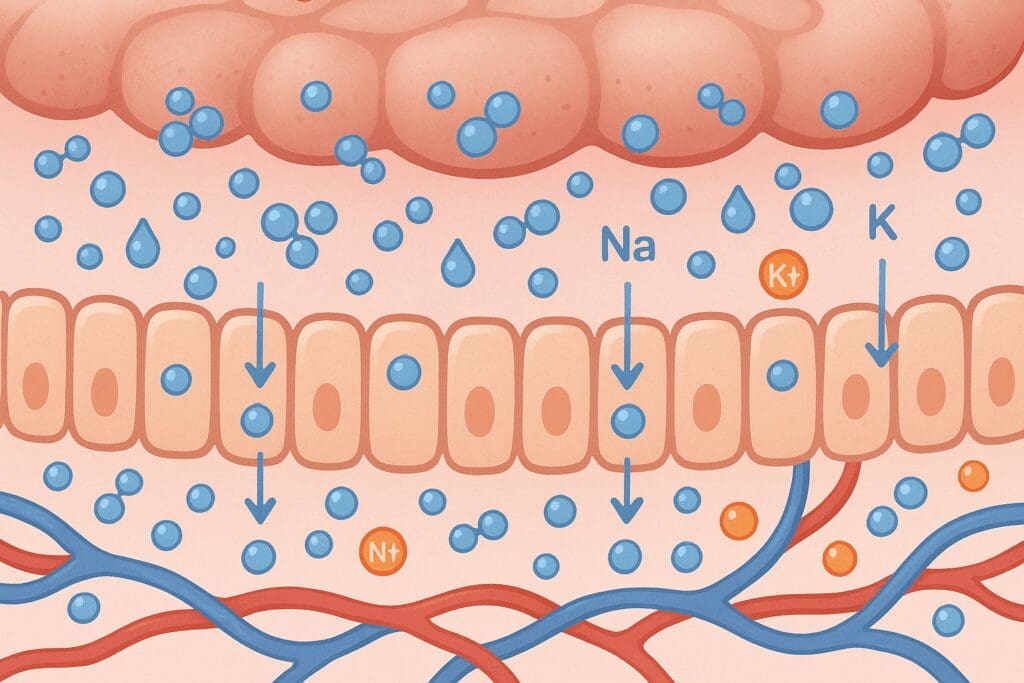

At its core, the primary function of the large intestine is to absorb water and electrolytes from indigestible food matter and to compact the resulting material into feces. This may seem like a straightforward task, but the physiological and biochemical processes involved are anything but simple. Water reabsorption alone involves intricate osmoregulatory mechanisms that prevent dehydration, especially critical in environments or situations where water is scarce or fluid loss is high.

Electrolytes like sodium, chloride, and potassium are also reclaimed in the large intestine, maintaining electrolyte balance and supporting vital cellular processes. This function becomes even more critical when one considers how electrolyte imbalance can affect cardiac rhythm, nerve conduction, and muscle function. Thus, the answer to what is the primary function of the large intestine extends beyond mere waste management; it encompasses a range of homeostatic activities essential to survival.

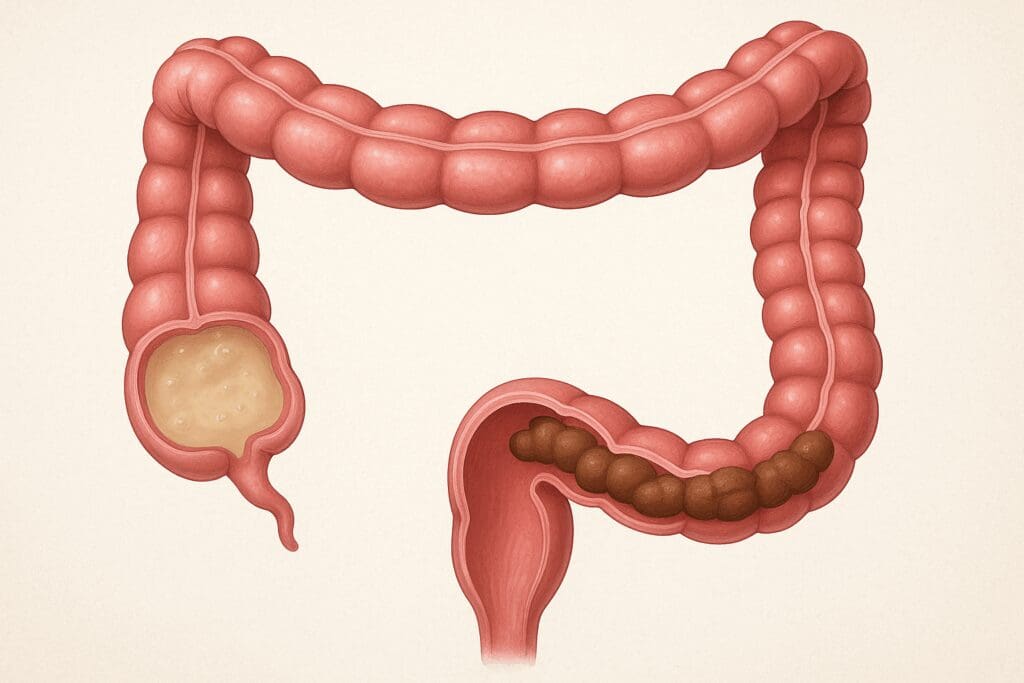

Another key element of large intestine function is its role in producing and storing feces. As undigested food material passes through the colon, it is dehydrated and compacted, forming the bulk material that will eventually be excreted. The rectum serves as a temporary storage site for feces, explaining where is faeces stored in the body. This storage function is crucial for voluntary bowel movements and for the body’s ability to delay defecation when necessary.

Microbial Marvels: How Gut Flora Amplifies Colon Health

The large intestine is home to a dense and diverse microbial community known as the gut microbiota. These microorganisms not only survive but thrive in this unique environment, performing functions that are symbiotic in nature. They ferment undigested carbohydrates into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like acetate, propionate, and butyrate, which provide energy to colon cells and have anti-inflammatory effects. This microbial activity enhances large intestine function and illustrates the deeper importance of asking not just what does the large intestine do, but also how it interacts with its microbial residents.

In addition to aiding in digestion, the microbiota plays a significant role in immune modulation. Over 70% of the immune system resides in the gut, and the large intestine serves as a key training ground for immune cells. Exposure to diverse microbes helps the immune system learn to differentiate between harmless antigens and genuine threats. This aspect of colon gut interaction is foundational to developing immune tolerance and preventing autoimmune disorders.

Furthermore, the microbiota helps synthesize essential nutrients such as vitamin K and certain B vitamins, adding yet another layer of importance to the colon. These contributions underscore that what does the big intestine do encompasses much more than simple waste removal. Instead, it serves as a dynamic environment that contributes to overall health in multifaceted ways.

The Components of the Large Intestine: A Coordinated System

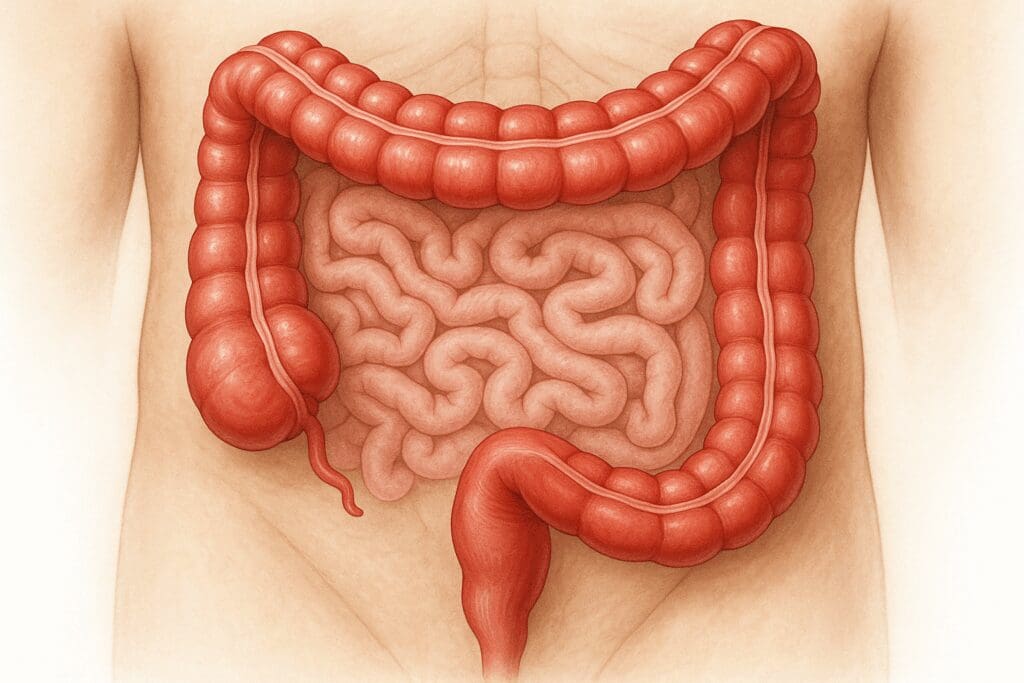

To understand the full spectrum of large intestine function, it’s helpful to break down the components of the large intestine and explore their individual roles. The cecum serves as the entry point from the small intestine and acts as a fermentation chamber where microbial activity begins. The ascending colon transports material upward along the right side of the abdomen, while the transverse colon moves it horizontally. The descending colon then shifts the waste downward, and the sigmoid colon curves it toward the rectum.

Each of these segments has specialized roles in mixing, storing, and dehydrating waste. The colon also engages in peristaltic movements to push material along its length. These coordinated contractions are influenced by neural and hormonal signals, which help regulate the timing and efficiency of waste processing. Recognizing the specialization of each part of the colon enriches our understanding of what is the large intestine do and why its function cannot be generalized.

The rectum, often an afterthought in digestive discussions, is critical in answering the question of where is feces stored. This muscular chamber can expand significantly to accommodate waste until defecation is socially and physiologically appropriate. Its sensory receptors send signals to the brain, initiating the urge to defecate. Thus, the rectum and anus form a sophisticated control system that allows humans to manage waste elimination with both conscious control and involuntary reflexes.

What Is the Primary Function of the Large Intestine in Electrolyte and Water Homeostasis?

Water and electrolyte reabsorption might seem like passive processes, but they are tightly regulated and energetically demanding. The colon reclaims up to 1.5 liters of water daily, converting liquid chyme into a more solid form. Sodium ions are actively transported across the colonic epithelium, creating an osmotic gradient that facilitates water absorption. Potassium and chloride ions are also regulated through specialized channels and pumps.

Disruption in these processes can lead to conditions like diarrhea or constipation. In cases of excessive water retention, feces become dry and difficult to pass, while insufficient water absorption results in loose stools and dehydration. Understanding what is the primary function of the large intestine in maintaining these balances can lead to better strategies for managing digestive disorders and optimizing hydration.

Electrolyte balance is equally critical. Sodium and potassium gradients are essential for nerve impulse transmission and muscle contraction. Any disruption in these gradients, especially during illness, can have cascading effects on cardiac and neuromuscular health. This understanding is vital when considering the implications of chronic conditions like irritable bowel syndrome or inflammatory bowel disease, where electrolyte handling is often compromised.

Colon Gut Health: The Intersection of Diet, Lifestyle, and Digestion

Colon gut health is not merely the absence of disease but the presence of a thriving, balanced internal environment. Diet plays an enormous role in shaping this environment. Fiber, both soluble and insoluble, serves as fuel for beneficial microbes and adds bulk to stools. Fermented foods introduce probiotics, while prebiotic foods like garlic, onions, and bananas nourish existing gut flora. Together, these dietary components support the main function of large intestine processes such as fermentation, waste transport, and water absorption.

Physical activity, hydration, and stress management also contribute significantly to colon health. Regular exercise stimulates intestinal motility, preventing constipation and encouraging microbial diversity. Hydration ensures that there is adequate water available for the colon to absorb, which helps maintain stool consistency. Stress, often overlooked, can profoundly affect gut motility and microbial balance through the gut-brain axis.

Lifestyle modifications, including better sleep and reduced alcohol intake, further support what does the large intestine do. Many people fail to realize that the health of the colon is intimately tied to overall well-being. For instance, sleep deprivation alters hormonal regulation, which can affect bowel habits and gut permeability. Similarly, alcohol disrupts the mucosal barrier and kills beneficial bacteria, leading to a compromised immune response and poor digestion.

What Is the Primary Function of the Large Intestine in Fecal Formation and Storage?

Fecal formation is not a haphazard process but a carefully coordinated sequence of dehydration, microbial activity, and muscular movement. As material enters the colon, it contains a significant amount of water, fiber, and undigested residues. Through the actions of the large intestine, this slurry is compacted into semisolid feces. Microbial fermentation contributes to the texture, odor, and nutritional content of the waste, further illustrating what is the purpose of the large intestine.

The final product is stored in the rectum, raising questions about where is poop stored and how the body decides when to release it. Rectal stretch receptors communicate with the central nervous system to regulate the defecation reflex. This complex communication ensures that elimination is timely and controlled. Dysfunction in this system can result in conditions like fecal incontinence or chronic constipation, both of which significantly affect quality of life.

Importantly, the composition of feces offers insights into gut health. Ideal stools are smooth, formed, and easy to pass, indicating a well-functioning colon. Changes in color, consistency, or frequency may signal underlying issues that require attention. Hence, observing one’s feces is a practical way to assess what is the large intestine do in maintaining health and equilibrium.

What Does the Large Intestine Do During Digestive Stress or Disease?

In states of disease or digestive distress, the functions of the large intestine can be significantly impaired. Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, disrupt mucosal integrity and immune function, leading to symptoms like abdominal pain, diarrhea, and blood in the stool. These conditions underscore the importance of understanding what is the primary function of the large intestine, as therapeutic interventions often aim to restore this very functionality.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), although not characterized by visible inflammation, affects motility and sensitivity in the colon. Patients often experience alternating bouts of constipation and diarrhea, reflecting the colon’s dysregulated role in water and electrolyte handling. These disorders highlight the need for individualized treatment plans that consider dietary triggers, stress management, and pharmacologic options.

Colon cancer is another serious condition that impacts large intestine function. Tumors can obstruct waste flow, alter absorption, and lead to systemic effects like weight loss and anemia. Early detection through screening methods like colonoscopies is crucial, especially for populations at higher risk. Treatment options range from surgery to chemotherapy, and preserving as much colon function as possible is often a key consideration.

The interplay between genetics, environment, and lifestyle becomes particularly evident in these scenarios. A person with a genetic predisposition to IBD may remain asymptomatic until triggered by environmental factors like diet, antibiotics, or stress. This complex causality underscores why an in-depth understanding of what does the big intestine do is essential for both prevention and treatment.

Navigating Disorders: How Understanding the Large Intestine Can Guide Treatment

In the landscape of gastrointestinal disorders, having a clear understanding of what is the primary function of the large intestine enables more targeted and effective interventions. For example, in cases of chronic constipation, treatment may begin with increasing dietary fiber and fluid intake, but understanding the underlying motility issues or electrolyte imbalances can guide the use of prokinetic agents or laxatives. These interventions should be aligned with the large intestine’s natural rhythm to avoid dependency or further dysregulation.

Similarly, in diarrhea-predominant conditions, the challenge lies in supporting water reabsorption. Medications that slow transit time or bind excess water in the colon are often employed. However, more nuanced strategies involve rebalancing gut flora through the use of probiotics and diet adjustments, reaffirming the centrality of the colon gut ecosystem in symptom relief. This holistic view acknowledges that what does the large intestine do is not limited to mechanical actions—it is part of a finely tuned symphony of biochemical and microbial processes.

Fecal transplants, once a fringe concept, have become a mainstream treatment for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infections. This cutting-edge approach relies on reintroducing healthy microbial communities into a dysfunctional colon, directly addressing the loss of microbial diversity. The success of such treatments underscores how essential the microbiome is to the overall large intestine function and gut health, and how modern medicine is increasingly leveraging this knowledge in practice.

Where Is Your Colon and Why Its Location Matters for Function

Understanding where is your colon located helps appreciate how its position influences its function. The large intestine wraps around the small intestine, framing it from the lower right abdomen (cecum) upward (ascending colon), across the upper abdomen (transverse colon), down the left side (descending colon), and finally curving into the pelvis (sigmoid colon and rectum). This arrangement allows gravity and muscular contraction to work together in propelling waste material in a logical sequence, supporting efficient fecal formation.

Location also affects diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. For instance, left-sided colon pain often signals issues like diverticulitis, while right-sided discomfort may be related to cecal inflammation or ascending colon disease. Colonoscopy procedures, which visualize the entire large intestine, are based on this anatomical layout and are crucial for detecting precancerous polyps, inflammation, or malignancies in specific segments.

The spatial orientation of the colon also explains the variable sensations people experience during digestion. Bloating in the transverse colon can cause discomfort under the rib cage, while rectal distension may create urgency or pain in the pelvic region. These anatomical insights bridge the gap between symptom perception and underlying pathology, making the knowledge of where is your colon not just academic, but clinically relevant.

What Is the Purpose of the Large Intestine in Nutrient Recovery?

While the small intestine is primarily responsible for absorbing nutrients like glucose, amino acids, and fatty acids, the large intestine also plays a role in nutrient salvage. Certain fibers and resistant starches that escape small intestinal digestion reach the colon, where they are fermented by bacteria into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). These SCFAs, especially butyrate, are absorbed into the bloodstream and used as energy, primarily by colonocytes, the cells lining the colon.

This form of nutrient recovery is not just efficient but critical. Butyrate has been shown to reduce inflammation, support cellular health, and even protect against colon cancer. This further reinforces the idea that what is the purpose of the large intestine extends into areas previously thought to be the sole domain of the small intestine. The colon, through microbial mediation, acts as a secondary site for energy production and nutrient utilization.

The production of certain vitamins, such as vitamin K2 and some B-complex vitamins, is also facilitated by gut bacteria residing in the colon. Although these nutrients are not absorbed in significant quantities compared to those from diet, their local availability contributes to intestinal health and function. This further complicates and enriches our understanding of what is the primary function of the large intestine, especially when considering its interactions with systemic metabolism and immune responses.

The Large Intestine and the Gut-Brain Connection

Recent scientific interest in the gut-brain axis has shed light on the profound ways in which the colon gut communicates with the central nervous system. Through pathways involving the vagus nerve, microbial metabolites, and inflammatory mediators, the large intestine sends and receives signals that influence mood, behavior, and cognitive function. Conditions like depression, anxiety, and even neurodegenerative diseases have shown associations with dysbiosis in the colon.

This emerging field demonstrates that understanding what does the large intestine do goes beyond its physical function and includes its role as a neuroendocrine organ. For instance, serotonin, a neurotransmitter involved in mood regulation, is largely produced in the gut. Disruptions in microbial populations can influence serotonin levels and, by extension, mental health.

Mindfulness practices, meditation, and stress reduction techniques have been shown to impact gut motility and microbial composition positively. The gut-brain connection operates bidirectionally: while gut health influences mental state, emotional well-being also affects gut physiology. Recognizing this interplay is critical for those managing both digestive and psychological conditions, offering a more integrated path to wellness.

Supporting a Healthy Colon: Practical Tips for Lifelong Gut Health

Given the centrality of the large intestine to health, maintaining its function should be a priority. First and foremost, a diet rich in fiber supports both motility and microbial diversity. Aim for a mix of soluble and insoluble fibers from fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains. These not only facilitate stool formation but also provide fermentable substrates for beneficial bacteria, enhancing the main function of large intestine ecosystems.

Probiotic foods like yogurt, kefir, and sauerkraut can introduce helpful strains of bacteria, while prebiotic foods such as leeks and asparagus help nourish them. Together, they contribute to a resilient and balanced microbiota, reinforcing what is the primary function of the large intestine in supporting digestion, immune function, and even mental health.

Staying hydrated is equally important, as water is essential for stool consistency and electrolyte transport. Regular exercise promotes gut motility and has been associated with greater microbial diversity. Stress management through yoga, deep breathing, or cognitive behavioral therapy can help reduce episodes of irritable bowel syndrome or functional constipation, making the entire digestive process more harmonious.

Avoiding overuse of antibiotics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is another practical step. These medications can damage the mucosal lining or disrupt microbial communities, undermining the colon’s delicate balance. In some cases, targeted supplementation with butyrate or resistant starches may be warranted to help restore equilibrium.

Frequently Asked Questions: Expert Insights into Large Intestine Function and Gut Health

What Is the Primary Function of the Large Intestine in Hormonal Regulation and How Does It Impact Overall Health?

Beyond digestion and waste elimination, the large intestine plays a critical but underappreciated role in hormonal regulation. Specialized cells in the colon gut release hormones like peptide YY (PYY) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), which influence satiety, glucose metabolism, and insulin sensitivity. These gut-derived hormones communicate directly with the pancreas and brain, linking digestive health with energy regulation and appetite control. Dysregulation of these hormonal signals may contribute to metabolic disorders such as obesity and type 2 diabetes. Recognizing this complex endocrine function broadens our understanding of what is the primary function of the large intestine and underscores its influence beyond the confines of digestion.

How Do the Components of the Large Intestine Influence Bowel Training and Habit Formation?

The segmented architecture of the colon—from cecum to rectum—plays a pivotal role in shaping consistent bowel habits. Each segment of the components of the large intestine contributes to timed propulsion and fecal formation, creating a rhythm that can be trained through behavioral cues. For example, responding to natural urges promptly can reinforce neuromuscular pathways that regulate rectal sensitivity and anal sphincter control. Ignoring these signals regularly, however, can lead to desensitization and conditions like chronic constipation or fecal impaction. Understanding the structure-function relationship of these components can help individuals develop healthier toileting routines and restore functional balance within the colon gut system.

In Terms of Detoxification, What Does the Large Intestine Do That the Liver Doesn’t?

While the liver handles chemical detoxification via enzymes and conjugation pathways, the large intestine supports mechanical and microbial detoxification. It binds toxins, heavy metals, and xenobiotics within fecal matter and expels them from the body—essentially functioning as a physical elimination route. Certain beneficial microbes in the colon gut even neutralize pathogenic bacteria and produce antimicrobial compounds that maintain gut integrity. This collaboration between microbial metabolism and mechanical clearance illustrates a unique aspect of large intestine function not mirrored by the liver. It answers what does the large intestine do in the context of detoxification: it complements chemical processing with direct removal.

What Is the Purpose of the Large Intestine in the Elderly and How Does Aging Affect Its Function?

Aging naturally brings changes to the motility and sensitivity of the colon, impacting how efficiently the body can handle digestion and waste. The muscle tone of the colon walls may weaken, reducing peristalsis and slowing transit time, often resulting in constipation. Additionally, the composition of the microbiome shifts with age, affecting microbial diversity and resilience. These changes influence nutrient salvage, inflammation levels, and even cognitive clarity, due to the gut-brain axis. Therefore, in elderly individuals, what is the purpose of the large intestine becomes increasingly focused on maintaining microbial equilibrium and effective elimination to preserve overall health and independence.

Where Is Your Colon Most Vulnerable to Disease and What Should You Watch For?

The sigmoid colon and rectum are particularly susceptible to disorders such as diverticulitis, polyps, and colorectal cancer due to the high pressure and frequent fecal contact in this region. This part of the colon gut is also where stool becomes most compacted, making it more likely to irritate the mucosal lining. Persistent changes in bowel habits, rectal bleeding, or unexplained weight loss should prompt immediate medical evaluation. Knowing where is your colon at risk empowers people to seek preventative screenings such as colonoscopies that can detect precancerous lesions early. Early detection and intervention are key to preserving optimal large intestine function throughout life.

What Is the Primary Function of the Large Intestine in Hydration Recovery Post-Diarrhea?

After episodes of diarrhea, the large intestine becomes essential in restoring fluid and electrolyte equilibrium. Specialized epithelial cells in the colon increase their absorptive capacity to re-capture water, sodium, and chloride. This ability is regulated by aldosterone, a hormone that upregulates sodium transporters during dehydration. This makes understanding what is the primary function of the large intestine vital during recovery from gastrointestinal illness. Rehydration strategies should thus include electrolyte-rich solutions to support the colon’s efforts and avoid complications such as hypovolemia or arrhythmia due to electrolyte imbalance.

Where Is Feces Stored Prior to Defecation and How Does This Affect Continence?

Feces are temporarily held in the rectum, which expands to accommodate varying volumes while communicating with the brain through stretch receptors. This answers the question of where is feces stored and highlights the rectum’s unique role as both a sensory and muscular organ. Pelvic floor muscles, the internal and external anal sphincters, and the puborectalis muscle work together to maintain continence and allow voluntary control over defecation. When these structures are compromised—as in pelvic surgery or neurological disease—continence may be lost, requiring targeted therapy or biofeedback training. Thus, where is poop stored is not just anatomical trivia; it’s central to quality of life and daily autonomy.

What Does the Big Intestine Do to Combat Opportunistic Infections?

The big intestine, or colon, plays a frontline role in defending the body against opportunistic pathogens. It does so through competitive exclusion, where commensal bacteria outcompete harmful invaders for nutrients and attachment sites. Moreover, some microbes produce bacteriocins—natural antibiotics that inhibit the growth of rivals. The mucus layer lining the colon also traps potential threats, while secreted immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibodies neutralize pathogens before they can invade. This defense system is a crucial answer to what does the big intestine do beyond digestion: it acts as an immune fortress that constantly patrols for microbial threats.

How Do Environmental Toxins Disrupt Large Intestine Function and What Can Be Done?

Environmental toxins like pesticides, plastics (BPA), and heavy metals can impair large intestine function by damaging the gut lining and altering microbial diversity. These substances compromise tight junction integrity, leading to increased intestinal permeability, often referred to as “leaky gut.” This condition can result in systemic inflammation and even autoimmune activation. One way to support recovery is through a diet high in polyphenols, found in berries, green tea, and dark chocolate, which can mitigate oxidative stress. Enhancing detoxification through fiber intake and reducing toxic exposure are vital strategies to preserve what is the large intestine do in maintaining gut and systemic resilience.

How Do the Components of the Large Intestine Collaborate During Sleep?

During sleep, the components of the large intestine continue to work, albeit at a slower rhythm. The colon exhibits a pattern known as the migrating motor complex (MMC), which clears residual waste and resets the gut environment. This nocturnal activity allows the colon gut to maintain its internal cleanliness and microbial balance. Disrupting sleep patterns, especially through night shift work or sleep apnea, can impair this cleansing process and lead to gastrointestinal symptoms like bloating or irregularity. Understanding the silent overnight collaboration of each colon segment offers a fascinating view into how what is the large intestine do isn’t limited to waking hours—it’s a 24/7 operation vital to health.

Conclusion: Why the Function of the Large Intestine Is Foundational to Gut Health and Overall Wellness

As we have explored, understanding what is the primary function of the large intestine reveals a network of interconnected roles that stretch far beyond waste elimination. From water and electrolyte balance to microbial fermentation, immune modulation, and even mood regulation, the colon serves as a critical hub of health and vitality. Every segment of this complex organ—from the cecum to the rectum—works in unison to ensure that our bodies remain hydrated, nourished, and protected.

When we ask what does the large intestine do or where is poop stored, we are not merely seeking anatomical trivia. We are delving into a sophisticated system that holds implications for everything from chronic disease prevention to mental well-being. In this light, the large intestine emerges not as an afterthought in the digestive process but as a key protagonist in the story of human health.

With greater public awareness and scientific understanding, we are now better equipped than ever to protect and enhance the function of this vital organ. By adopting supportive lifestyle habits, seeking medical advice when symptoms arise, and recognizing the colon’s many contributions, we honor the profound importance of gut health. In doing so, we reinforce not just the vitality of our digestive system but the resilience of our entire being. Understanding and supporting what is the primary function of the large intestine may well be one of the most impactful decisions we can make for lifelong health.