For countless new mothers, the journey into breastfeeding begins with high hopes and natural assumptions about its simplicity. After all, it’s the most primal form of nourishment. Yet for many, the lived experience diverges dramatically from expectation. The question surfaces with rising urgency in postpartum forums, clinical consultations, and intimate late-night moments: why is it so hard to breastfeed? Despite being a biologically designed process, breastfeeding often presents a myriad of unforeseen challenges—ranging from latch issues to emotional overwhelm. These struggles are not merely anecdotal; they reflect systemic, physiological, and psychological complexities that have real implications for both mother and baby.

To truly comprehend the difficulty of breastfeeding, one must consider the interplay of hormonal responses, infant behavior, maternal anatomy, social support structures, and the modern medical landscape. Too often, new mothers feel blindsided by breastfeeding difficulties, having never been fully prepared for the possibility of complications. As a result, they may internalize these struggles as personal failures, fueling a cycle of guilt, anxiety, and even postpartum depression. This article seeks to demystify the many layers behind the breastfeeding experience. With insights grounded in medical evidence and informed by maternal narratives, it aims to offer not only clarity but also empowerment. Whether you’re a first-time mom or a seasoned parent seeking answers, understanding why breastfeeding is hard is the first step toward overcoming those challenges with confidence and care.

You may also like: 7 Surprising Breastfeeding Facts Every New Mom Should Know for a Confident Start

Anatomy, Physiology, and the Unexpected: The Biological Roots of Breastfeeding Problems

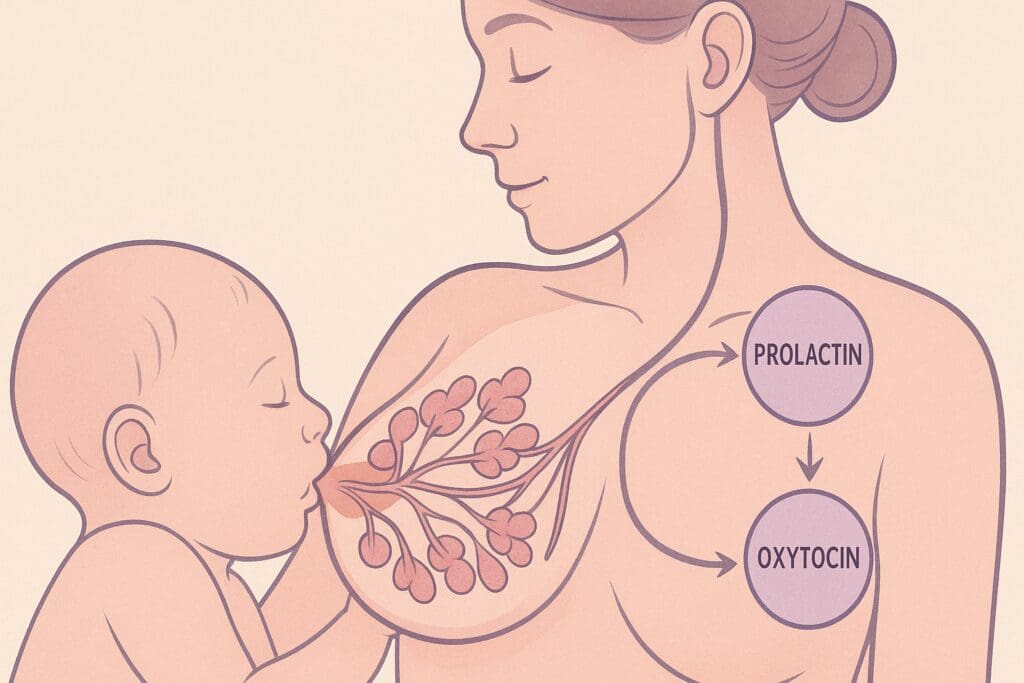

Breastfeeding is often romanticized as an instinctive process that occurs seamlessly once a baby is born. However, its success depends on an intricate web of physiological events that must align precisely. At the heart of lactation is the mammary gland’s ability to produce, store, and eject milk in response to the baby’s suckling. This process is governed by a cascade of hormonal signals—primarily prolactin and oxytocin. Prolactin stimulates milk production, while oxytocin triggers the let-down reflex, which releases milk from the ducts to the nipple.

Despite this biological blueprint, any number of disruptions can lead to lactation problems. For instance, retained placenta fragments after delivery can delay the drop in progesterone necessary for prolactin to activate. Infections, such as mastitis or thrush, can create physical pain that discourages continued feeding. Additionally, certain anatomical variations like flat or inverted nipples, tongue-tie in the infant, or insufficient glandular tissue (IGT) in the mother may interfere with the infant’s ability to latch effectively or drain the breast fully. These issues often go undiagnosed or misunderstood, causing a cascade of lactation difficulties.

Modern obstetric practices can also unwittingly contribute to mother feeding problems. Routine separations of mother and infant after birth, delayed initiation of breastfeeding, and reliance on formula supplementation in hospitals all interfere with the natural cues and supply-demand cycle critical to successful breastfeeding. These institutional barriers compound pre-existing breastfeeding issues, leaving mothers to grapple with not only their own expectations but also systemic impediments. Recognizing these biological and structural factors helps reframe the narrative: breastfeeding problems are not maternal shortcomings but complex medical realities that warrant informed care and support.

Pain, Exhaustion, and Frustration: The Tangible Reality of Breastfeeding Difficulties

Pain is one of the most commonly reported reasons why mothers struggle to continue breastfeeding, and yet it remains one of the least anticipated aspects for many. From cracked nipples and engorgement to deep breast pain caused by blocked ducts or infections, the physical toll of breastfeeding is frequently underestimated. For women already recovering from childbirth—whether vaginal or cesarean—this added layer of pain can become a major deterrent. Lactation difficulties aren’t simply inconveniences; they can be severe enough to interfere with daily functioning and emotional stability.

Exhaustion compounds the challenge. Newborns feed frequently—often every two to three hours, including through the night. This schedule does not adhere to adult circadian rhythms, and the cumulative sleep deprivation can lead to cognitive fog, irritability, and diminished coping abilities. When combined with frustration over poor latch, low milk supply, or infant fussiness at the breast, many mothers find themselves overwhelmed by the demands of breastfeeding. These factors intertwine, amplifying the stress and feelings of inadequacy many women face in the early postpartum period.

Additionally, not all babies are born with equal readiness to breastfeed. Premature infants, for instance, may lack the muscle tone or coordination required for effective suckling. Even full-term babies can present breastfeeding issues due to birth trauma, jaundice, or congenital conditions such as cleft palate. This means that the difficulties experienced are not always on the maternal side, but often a complex dynamic between mother and baby. Understanding this broader picture is critical in moving away from blame and toward effective breastfeeding troubleshooting. Pain, fatigue, and emotional distress are not signs of failure; they are calls for support and intervention that should be met with empathy and clinical expertise.

The Mental Load: Psychological and Emotional Factors Behind Why Breastfeeding Is So Hard

While physical barriers are more visible, the psychological and emotional dimensions of breastfeeding can be just as debilitating. The societal idealization of breastfeeding creates a kind of cultural pressure that can weigh heavily on new mothers. Media portrayals, parenting blogs, and even well-intentioned relatives often paint an idyllic picture that omits the common struggles. When reality falls short of this ideal, mothers may internalize their breastfeeding problems as personal shortcomings. This emotional toll can manifest as guilt, shame, anxiety, or depressive symptoms—all of which can further inhibit lactation.

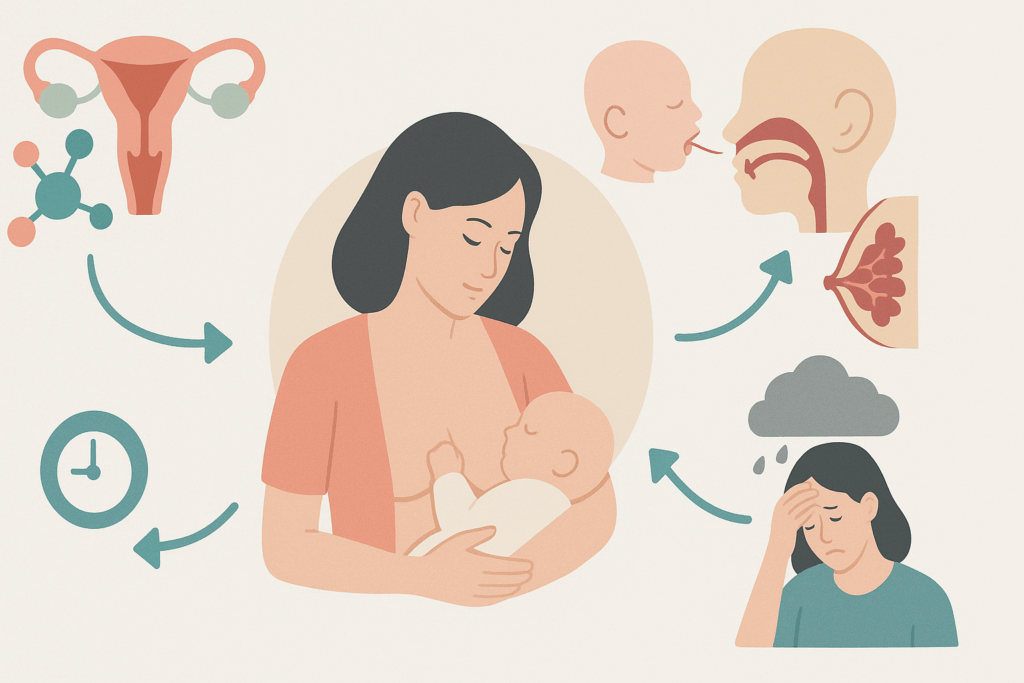

Hormonal fluctuations postpartum can intensify these psychological struggles. The rapid drop in estrogen and progesterone after childbirth has a well-documented impact on mood regulation. For mothers experiencing challenges in breastfeeding, this neurochemical shift can magnify feelings of helplessness. Moreover, the oxytocin released during breastfeeding—often referred to as the “love hormone”—can have complex effects. While it’s known to promote bonding, oxytocin also makes mothers more emotionally sensitive, potentially deepening the pain of perceived failure.

Support—or the lack thereof—plays a vital role in navigating these emotional waters. Women without access to lactation consultants, peer support groups, or even empathetic family members may feel isolated in their breastfeeding journey. This isolation can exacerbate emotional stress and diminish the resolve to continue breastfeeding, even in the absence of significant physical issues. Conversely, women who receive validation, guidance, and reassurance often report better coping mechanisms and a more positive outlook. Recognizing that lactation issues breastfeeding are not merely mechanical but deeply emotional allows for a more holistic approach to care and communication.

Lack of Preparation and Misinformation: Why Is It So Hard to Breastfeed Without the Right Education?

One of the most glaring contributors to early breastfeeding problems is the widespread lack of preparation. While expectant mothers often attend childbirth classes and meticulously plan their labor experiences, breastfeeding education is frequently overlooked or offered in limited, oversimplified formats. Hospitals may provide basic pamphlets or brief lactation overviews, but these rarely cover the complexities of real-world breastfeeding issues. As a result, many mothers enter the postpartum period unarmed for the unpredictable and often difficult path ahead.

A fundamental misconception is that breastfeeding is automatic—that both mother and baby will instinctively know what to do. While the suckling reflex is innate in newborns, effective breastfeeding is a learned skill for both parties. Mothers must understand proper latch techniques, feeding cues, milk supply regulation, and how to navigate common breastfeeding ailments. Without prior exposure to this knowledge, many struggle during those critical first days, often without knowing that their difficulties are entirely normal and resolvable.

Misinformation adds further barriers. Popular myths—such as the belief that pain is a necessary part of breastfeeding, or that low milk supply is inevitable—perpetuate harmful narratives. Some sources wrongly equate formula use with failure, intensifying the emotional weight on mothers who supplement. Conversely, others downplay the benefits of breastfeeding entirely, offering little incentive for mothers to persist through early challenges. These conflicting messages leave new parents confused and unsupported in their decision-making.

Moreover, cultural influences and generational beliefs often shape breastfeeding expectations in counterproductive ways. In some communities, formula feeding may be the norm, leading to stigma or skepticism around exclusive breastfeeding. In others, pressure to breastfeed without adequate support leads to silent suffering. Education must be contextualized, evidence-based, and comprehensive, equipping parents with both the confidence and competence to make informed decisions. Only then can the question—why is it so hard to breastfeed—begin to find answers grounded in preparation rather than panic.

Breastfeeding Troubleshooting: Effective Solutions for Common Lactation Difficulties

The good news is that while breastfeeding problems are common, many are highly treatable with timely intervention. Successful breastfeeding troubleshooting begins with accurate assessment. Lactation consultants are trained to evaluate latch quality, infant suck efficiency, and maternal breast anatomy to identify where the breakdown is occurring. Often, a simple adjustment in positioning or technique can alleviate nipple pain or improve milk transfer significantly. Tools like nipple shields or syringe feeding can also offer short-term relief while underlying issues are addressed.

Addressing milk supply concerns—one of the most frequently cited breastfeeding difficulties—requires an understanding of the supply-and-demand principle. In most cases, increasing the frequency of nursing or adding pumping sessions can stimulate additional production. However, underlying medical conditions like hypothyroidism or retained placenta may interfere with supply and require targeted medical management. Similarly, signs of oversupply, such as frequent leaking or infant choking during feeds, can be corrected through block feeding or paced bottle techniques.

For mothers dealing with infections like mastitis or fungal overgrowth, appropriate treatment is crucial to prevent further complications. Mastitis may require antibiotics and cold compresses, while fungal infections like thrush necessitate antifungal creams and infant treatment. Ductal issues, such as blockages or blebs, benefit from warm compresses, massage, and adjusting feeding positions to ensure complete drainage.

In cases of infant-related lactation problems, such as tongue-tie or weak suck reflex, collaboration with pediatricians, speech therapists, or ENT specialists may be needed. Surgical correction or targeted oral therapy can dramatically improve feeding outcomes. The key is individualized care: no two breastfeeding journeys are the same, and solutions must be tailored to the specific dyad. With proper support, even the most daunting breastfeeding issues can be overcome—transforming the experience from distressing to empowering.

Why Is It So Hard to Breastfeed in the Modern World? Cultural and Institutional Obstacles

While biology and individual challenges play a significant role, broader societal factors cannot be ignored when exploring why breastfeeding is hard in today’s world. One of the primary barriers is the cultural shift away from communal parenting. In past generations and many traditional cultures, new mothers were surrounded by a network of women—mothers, aunts, grandmothers—who offered hands-on help and guidance. Today, many mothers face the postpartum period in relative isolation, often without the multigenerational wisdom that once normalized and supported breastfeeding.

The structure of modern employment compounds this isolation. In countries with limited maternity leave or inadequate workplace accommodations, returning to work soon after childbirth becomes a major disruptor to breastfeeding continuation. Pumping in unsanitary or stressful environments, lack of refrigeration access, and fear of judgment from coworkers all contribute to lactation difficulties in professional settings. Although laws protecting breastfeeding rights exist in many regions, their enforcement and cultural acceptance vary widely, leaving many mothers to navigate workplace lactation issues breastfeeding alone and unsupported.

Additionally, the commercialization of infant feeding has left an indelible mark on societal perceptions. The widespread availability and aggressive marketing of formula in the 20th century eroded public knowledge about breastfeeding. As a result, generations of families grew up without firsthand exposure to nursing norms. This cultural amnesia is evident in healthcare systems, where many providers receive limited lactation training and may be ill-equipped to support complex breastfeeding problems. Furthermore, public discomfort with nursing—especially beyond infancy or in public settings—reinforces stigma and discourages mothers from fully embracing their breastfeeding goals.

To combat these institutional and cultural challenges, systemic change is necessary. This includes expanding access to certified lactation professionals, implementing paid parental leave, and fostering breastfeeding-positive public spaces. Equally important is restoring breastfeeding visibility in media, education, and community programs. When society normalizes breastfeeding and invests in its success, mothers are better positioned to overcome the question of why is breastfeeding so difficult with resilience and confidence.

Medical Conditions That Disrupt Lactation: When Breastfeeding Problems Have a Clinical Origin

In some cases, breastfeeding issues arise from underlying medical conditions that interfere with lactation, milk transfer, or maternal stamina. One commonly overlooked factor is insufficient glandular tissue (IGT), a condition in which a woman’s breasts do not have enough milk-producing glands to generate a full supply. While rare, IGT can lead to persistent low milk production despite frequent nursing and pumping. Visual signs include widely spaced breasts, asymmetry, or lack of breast changes during pregnancy or postpartum. Diagnosis often requires careful evaluation by a lactation consultant and healthcare provider.

Hormonal imbalances also play a significant role. Conditions such as hypothyroidism, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), and diabetes can all disrupt the hormonal signals required for milk production. Even subtle imbalances may result in sluggish milk let-down or delayed onset of lactogenesis II (the hormonal shift that occurs two to five days after birth). Identifying and treating these endocrine disorders can significantly improve breastfeeding outcomes, but too often they go undetected, leaving mothers to struggle without understanding the cause.

Maternal mental health is another critical factor. Postpartum depression and anxiety can interfere with breastfeeding through multiple pathways. Biologically, elevated cortisol levels can blunt oxytocin release, impairing milk ejection. Behaviorally, mood disorders reduce motivation and stamina, making it difficult for mothers to adhere to frequent feeding schedules or seek help when needed. In some cases, medication used to manage these conditions may further impact milk supply, necessitating careful coordination between providers.

For infants, medical issues such as tongue-tie, cleft lip or palate, neurological disorders, and hypotonia can all present breastfeeding challenges. These conditions affect the infant’s ability to latch, create suction, or sustain a rhythmic suck-swallow-breathe pattern. Early diagnosis and multidisciplinary care—including lactation consultants, pediatricians, and therapists—can help optimize feeding strategies, whether through direct nursing, pumping, or alternative supplementation methods.

Why Is It So Hard to Breastfeed Even When You’re Doing Everything Right?

Perhaps one of the most demoralizing aspects of the breastfeeding journey is encountering persistent difficulty despite following every recommended guideline. Many mothers attend prenatal classes, seek professional lactation help, nurse on demand, maintain a nutritious diet, and still face obstacles. The question arises again, sometimes in whispered desperation: why is it so hard to breastfeed even when I’m doing everything right? The answer lies in the inherent variability of human biology and the limits of personal control within a complex system.

Not all bodies respond identically to breastfeeding stimuli. While the hormone prolactin typically increases with frequent nursing, some women’s bodies respond sluggishly or require external stimulation like power pumping. Milk production is not only about effort—it also involves genetics, hormone sensitivity, and prior reproductive history. A first-time mother may struggle with low output that corrects in later pregnancies due to increased glandular development. Meanwhile, other mothers may face oversupply, leading to clogged ducts or infant gas and discomfort—despite doing everything “right.”

The infant’s role is equally crucial. A baby’s latch, oral anatomy, neurological maturity, and feeding temperament all influence the breastfeeding dynamic. Even in optimal conditions, feeding challenges may arise simply due to an infant’s unique development or temperament. Some babies are sleepy feeders; others are distractible or have erratic hunger cues. It is also not uncommon for infants to prefer one breast over the other or to fuss during let-down if milk flow is too fast or too slow. These variations are often biologically normal but can feel like mysterious obstacles without clear solutions.

External stress also undermines even the most well-planned breastfeeding routines. Lack of sleep, return to work, partner relationship strain, or the pressure to perform as a “perfect mom” all interfere with hormonal balance and milk ejection. When mothers are told that breastfeeding is natural and instinctive, these difficulties can feel deeply invalidating. Yet they are not a reflection of maternal failure—they are reminders that breastfeeding is a dynamic, evolving relationship. Persistence, adaptation, and compassionate support are more valuable than perfection. Recognizing that doing everything “right” doesn’t always yield instant success helps mothers give themselves grace in the face of unpredictable lactation issues breastfeeding.

Hidden Barriers: Social Inequities and Racial Disparities in Breastfeeding Support

One of the lesser-discussed reasons why breastfeeding is hard lies in systemic inequities that affect access to resources, support, and care. Research consistently shows that women from marginalized communities face disproportionately higher rates of breastfeeding problems. Black women in the United States, for instance, have significantly lower breastfeeding initiation and duration rates compared to their white counterparts. This disparity is not due to lack of will or education—it reflects structural barriers rooted in racism, socioeconomic inequality, and healthcare bias.

Hospitals serving predominantly Black and Brown communities often lack Baby-Friendly certifications or fail to provide comprehensive lactation services. Implicit bias may lead to assumptions about feeding preferences, resulting in fewer breastfeeding resources being offered. Meanwhile, historical trauma—particularly the exploitation of enslaved women as wet nurses—has left lingering mistrust around institutional medical guidance on breastfeeding. These layered experiences influence how women from different backgrounds perceive, approach, and continue breastfeeding.

Socioeconomic status also plays a critical role. Women working low-wage jobs are less likely to receive paid maternity leave, and therefore may be forced to return to work within weeks of delivery. These constraints make it nearly impossible to establish or maintain breastfeeding routines. Lack of private pumping spaces, inflexible schedules, and unsupportive work environments further compound the difficulty. Even something as simple as access to quality breast pumps, milk storage bags, or transportation to lactation appointments can become insurmountable hurdles for economically disadvantaged mothers.

Addressing breastfeeding difficulties in these populations requires culturally sensitive, community-based interventions. Peer counselor programs, home-visiting lactation support, and expanded Medicaid coverage for lactation services are proven strategies that help close the gap. It’s not enough to offer generic advice—we must dismantle the structural inequities that make breastfeeding disproportionately hard for certain groups. Only by addressing these hidden barriers can we ensure that every mother, regardless of race or income, has a fair chance at breastfeeding success.

The Social Stigma of Breastfeeding in Public and Extended Nursing

Even when breastfeeding is physically manageable, societal attitudes can create an invisible wall of resistance. One of the most pervasive cultural obstacles is the discomfort or judgment surrounding public breastfeeding. Many mothers report being stared at, asked to cover up, or even told to leave restaurants or stores while feeding their baby. This sends a damaging message that breastfeeding—an essential biological function—is somehow shameful or inappropriate. As a result, many women limit outings, plan their schedules around feedings, or switch to bottle-feeding in public to avoid confrontation.

This stigma also extends to breastfeeding beyond infancy. Despite recommendations from the World Health Organization and the American Academy of Pediatrics supporting breastfeeding up to two years and beyond, societal acceptance often wanes after the first year. Mothers who practice extended nursing may be labeled as overindulgent, overly attached, or even psychologically harmful to their child. These unfounded beliefs are rooted in cultural discomfort rather than science. Yet they exert real pressure, causing many mothers to wean prematurely or hide their feeding choices from others.

Such social scrutiny undermines confidence and autonomy. When mothers feel judged for feeding their babies, the emotional burden adds to an already demanding task. The internal question—why is it so hard to breastfeed—expands to include not just the act of nursing, but the social cost of doing so openly and proudly. Education campaigns, public breastfeeding protections, and inclusive media portrayals are essential steps toward normalizing this natural act. Changing societal perceptions may be one of the most powerful ways to ease the breastfeeding journey for future generations.

Navigating Partner Roles, Family Dynamics, and Shared Responsibility

Breastfeeding, by its nature, places a unique physical demand on the mother, but this should not translate to a one-person burden. The role of partners and family members is often underestimated, yet their involvement can significantly influence breastfeeding outcomes. When partners are engaged, informed, and supportive, mothers report higher satisfaction and longer breastfeeding durations. Conversely, when partners express doubt, disinterest, or lack of understanding, mothers may feel isolated, pressured, or undervalued.

Support can take many forms. Practical help—such as bringing the baby to the mother for night feeds, preparing snacks, cleaning pump parts, or managing household tasks—allows mothers to conserve energy for feeding. Emotional support is equally vital. Offering encouragement, validating her effort, and avoiding unsolicited advice or criticism builds trust and confidence. Even in families where breastfeeding is unfamiliar, partners who take the initiative to learn can bridge gaps and foster a nurturing environment.

Extended family dynamics also play a role. Grandparents, in-laws, or siblings may hold outdated views on feeding practices, unintentionally undermining the mother’s efforts. Comments like “we used formula and you turned out fine” or “he’s probably still hungry after nursing” can erode confidence. Managing these interactions requires setting boundaries, sharing evidence-based information, and sometimes choosing distance from unhelpful voices. Empowering mothers means reinforcing that their choices are valid and deserving of respect.

Creating a culture of shared responsibility around infant feeding transforms the breastfeeding experience. It communicates to the mother that she is not alone, that her effort is seen, and that the family unit stands beside her. Redefining breastfeeding as a family-centered practice rather than a solo endeavor helps dismantle the myth that its challenges are hers to bear alone.

Reframing Success: Redefining What It Means to “Breastfeed Successfully”

Amid the widespread challenges and lactation issues breastfeeding mothers face, it’s essential to rethink what constitutes a successful breastfeeding journey. Too often, success is narrowly defined by exclusivity and duration—creating rigid expectations that leave little room for nuance. A mother who weans at three weeks due to unbearable pain or mental health strain may feel like she has failed. One who supplements with formula may perceive her milk as inadequate. These internalized beliefs are not only unhelpful but also deeply misaligned with medical understanding and compassionate care.

Success should instead be measured by informed decision-making, maternal well-being, and infant health—regardless of the feeding method. If breastfeeding is contributing to physical pain, emotional breakdown, or family strain, then reevaluating the feeding plan can be a responsible and healthy choice. For some mothers, combination feeding is the most sustainable option. For others, exclusive pumping offers a middle path. And in many cases, switching to formula can restore emotional balance and enhance bonding, which is just as vital for infant development.

Clinicians and lactation professionals play a critical role in this reframing. By validating a wide range of feeding choices and avoiding prescriptive ideals, they help mothers feel empowered rather than judged. Support must be individualized, culturally sensitive, and rooted in the family’s unique context. Offering empathy rather than dogma allows for a more inclusive understanding of mother feeding problems and their resolution.

Redefining success also means acknowledging the silent wins: every ounce pumped, every hour comforted at the breast, every moment a mother trusted her instincts. Breastfeeding problems do not erase these victories. They highlight the complexity and resilience of mothers doing their best with the information, tools, and support they have. This shift in perspective can be liberating, replacing guilt with grace and helping mothers to honor their efforts with the respect they deserve.

Why Is Breastfeeding So Hard? Lessons from Global Health Models and Cross-Cultural Wisdom

To further understand why breastfeeding is hard in certain contexts, it’s useful to explore global health models where breastfeeding outcomes are markedly better. In Scandinavian countries, for instance, extended paid maternity leave, generous paternity leave, and universal healthcare create environments where breastfeeding is not only normalized but fully supported. Sweden, Norway, and Finland boast some of the highest breastfeeding continuation rates globally—not because their women are biologically different, but because the infrastructure around them facilitates success.

Contrast this with countries lacking maternity protections or affordable lactation support. In these regions, mothers are often forced to choose between economic survival and breastfeeding goals. The problem isn’t motivation—it’s system design. When health systems, governments, and employers invest in breastfeeding, they affirm its value. And when they don’t, the burden falls entirely on mothers, increasing the prevalence of breastfeeding difficulties and lactation problems.

Cultural practices also offer valuable insight. In many East African, South Asian, and Indigenous American communities, postpartum confinement periods provide mothers with round-the-clock help, warm foods to support milk production, and culturally embedded breastfeeding knowledge. These practices buffer against many early breastfeeding problems by prioritizing maternal rest and nourishment. While not every tradition may be directly transferable, the underlying principle—supporting the mother to feed the baby—transcends borders.

Global health lessons also show the danger of aggressive formula marketing in low-income countries. In places where access to clean water is limited, formula use can be life-threatening. Yet multinational corporations continue to market formula as superior or more modern, eroding confidence in breastfeeding and contributing to poor infant outcomes. These global dynamics remind us that breastfeeding success is not just a personal feat—it is a public health issue, an economic justice issue, and a human rights issue.

A Call for Compassion: Supporting the Mother Behind the Method

Ultimately, the conversation around breastfeeding must shift from performance to compassion. Mothers are not machines—they are complex beings recovering from one of life’s most profound physical and emotional transformations. Feeding an infant is just one part of a much larger story, which includes healing, identity formation, sleep deprivation, shifting relationships, and the overwhelming responsibility of caring for a new life. Asking why is it so hard to breastfeed is not a sign of weakness—it is a brave act of reflection, a plea for understanding, and a challenge to all of us to do better.

Compassion means listening without judgment when a mother cries about her cracked nipples. It means providing resources without strings attached when she says she’s struggling with supply. It means acknowledging the courage it takes to breastfeed in a culture that too often ignores or stigmatizes that effort. Compassion also extends to providers, partners, employers, and society at large. When we support the people supporting babies, we create ecosystems of care that benefit everyone.

No single strategy will eliminate breastfeeding ailments or solve every case of lactation problems breastfeeding. But by combining evidence-based care with emotional validation, we create space for healing, growth, and ultimately, empowerment. A mother who feels seen is a mother who can make choices that reflect her values and meet her baby’s needs—whether those involve breastfeeding for two days, two months, or two years.

FAQ: Expert Answers to Common Breastfeeding Challenges

Why Is It So Hard to Breastfeed When It’s Supposed to Be Natural?

Although breastfeeding is biologically designed, it is not automatically intuitive for either the mother or the baby. Successful nursing depends on a precise coordination of hormonal responses, anatomical compatibility, and behavioral learning—none of which are guaranteed without support. Many women experience breastfeeding ailments such as engorgement, cracked nipples, or slow milk let-down that undermine the process early on. Meanwhile, newborns may have difficulty latching or coordinating suck-swallow-breathe rhythms, especially if born prematurely or with subtle neurological immaturity. The idea that something natural should be easy sets unrealistic expectations, contributing to frustration when real-life breastfeeding difficulties inevitably arise.

How Can I Tell If My Baby’s Feeding Difficulties Are Due to Lactation Problems or Medical Issues?

Distinguishing between common lactation problems and underlying medical concerns requires close observation and, often, professional evaluation. Persistent signs like poor weight gain, excessively long feeding sessions, weak suck, or clicking sounds during nursing may indicate anatomical or neurological issues such as tongue-tie or hypotonia. On the maternal side, recurring clogged ducts, mastitis, or persistently low supply may point to endocrine disorders like PCOS or thyroid dysfunction. In these cases, basic breastfeeding troubleshooting may not be enough and should be complemented by consultations with pediatricians, lactation consultants, or other specialists. Prompt assessment allows for tailored intervention and prevents prolonged stress associated with unresolved mother feeding problems.

Why Is It So Hard to Breastfeed Even with Professional Help?

There are instances when even the most well-trained lactation consultant may not be able to resolve the issue fully, particularly when structural, hormonal, or mental health factors are involved. For example, some breastfeeding issues stem from subtle hormonal imbalances or undiagnosed postpartum anxiety, both of which interfere with milk let-down and maternal comfort. In these cases, success depends on a multidisciplinary approach involving mental health providers, endocrinologists, and occupational therapists. Additionally, gaps in breastfeeding education among healthcare professionals can sometimes lead to incomplete or outdated advice, leaving families discouraged. Persistence, second opinions, and integrated care models are essential for addressing the deeper layers of lactation difficulties.

Are There Preventive Strategies for Minimizing Breastfeeding Problems Before Birth?

Yes, preparation during pregnancy can significantly reduce the onset of early breastfeeding difficulties. Attending evidence-based prenatal lactation classes that include hands-on demonstrations and real-world troubleshooting scenarios is an excellent first step. Additionally, prenatal consultations with lactation consultants—especially for mothers with a history of breast surgeries, hormonal disorders, or flat/inverted nipples—can help identify and plan for potential lactation problems. Establishing postpartum support networks in advance, such as local peer groups or online forums, ensures mothers have someone to turn to during the early struggles. Finally, advocating for baby-friendly hospital policies at the delivery facility, including immediate skin-to-skin contact and rooming-in, creates an environment more conducive to breastfeeding success.

What Role Do Emotions and Trauma Play in Breastfeeding Difficulties?

Psychological factors play a surprisingly significant role in breastfeeding outcomes. Women with a history of birth trauma, childhood abuse, or past feeding challenges with older children may experience anxiety, hypervigilance, or even aversion when attempting to nurse. This emotional distress can disrupt oxytocin flow, impairing let-down reflexes and contributing to perceived lactation issues breastfeeding. In these cases, trauma-informed lactation support, somatic therapy, or gentle exposure techniques can provide critical relief. It’s also essential to normalize a broad range of emotional responses to breastfeeding—acknowledging that not every mother experiences joy or bonding through nursing, and that alternate feeding methods can still support a healthy parent-child connection. Treating emotional health as integral to lactation health can prevent burnout and long-term disengagement.

Why Is Breastfeeding So Difficult for Working Mothers?

Returning to work presents one of the most abrupt interruptions to breastfeeding continuity. Pumping schedules rarely align with rigid office breaks, and inadequate workplace accommodations—such as lack of privacy or refrigeration—exacerbate lactation problems breastfeeding. The stress of multitasking between job responsibilities and milk expression often leads to supply dips, particularly when compounded by insufficient sleep and commuting demands. Beyond logistics, many working mothers encounter social discomfort or even subtle discouragement from colleagues, making it harder to sustain the emotional resilience needed for continued lactation. Solutions include advocating for flexible pumping arrangements, educating employers on legal protections, and exploring hybrid feeding plans that combine direct nursing with pumping or formula as needed.

How Can Partners Support Breastfeeding Without Feeling Excluded?

Partners often struggle to find their place in the breastfeeding equation, especially when the focus is heavily maternal. However, their support can profoundly affect maternal well-being and lactation outcomes. Emotional validation, sharing night-time responsibilities like diaper changes or burping, and managing household chores all free up the breastfeeding mother’s physical and mental bandwidth. Partners can also learn about breastfeeding difficulties, observe for signs of lactation issues breastfeeding, and accompany mothers to lactation appointments for a more unified approach. This inclusion helps partners feel connected and ensures the mother does not bear the emotional and logistical weight of breastfeeding alone. When breastfeeding is viewed as a family effort, rather than a solo task, it becomes more sustainable.

Why Is It So Hard to Breastfeed in Public Without Judgment?

Societal discomfort with public breastfeeding reflects a broader sexualization of the female body and a misunderstanding of infant feeding as a private or shameful act. This stigma discourages mothers from feeding outside the home, potentially disrupting infant hunger cues and maternal supply patterns. It can also heighten maternal anxiety, leading to avoidance of social outings and isolation during a vulnerable life phase. Public backlash often stems from cultural norms, media portrayals, and a lack of exposure to breastfeeding as a normal part of everyday life. To counter this, visible support through public health campaigns, breastfeeding-friendly signage, and positive media representation can normalize the act. Confidence-building workshops can also empower mothers to breastfeed on their own terms without fear or apology.

What Innovations Are Emerging to Address Breastfeeding Ailments and Support Lactation?

Several emerging technologies and community models are reshaping how we approach breastfeeding troubleshooting and lactation support. Wearable breast pumps with smart sensors now offer discreet, on-the-go pumping with data tracking features that help mothers monitor output and trends. Meanwhile, AI-powered lactation apps provide tailored guidance, track feeding sessions, and offer real-time feedback on latch quality using photo and video assessments. Community milk-sharing programs, peer lactation networks, and telehealth lactation consultants have expanded access, especially in rural or underserved areas. Research is also advancing into lactogenic foods, probiotics, and herbal supplements designed to support milk production without pharmaceutical intervention. These innovations underscore a growing acknowledgment that breastfeeding is hard and deserves modern, multifaceted solutions.

Why Is It So Hard to Breastfeed Consistently Through Growth Spurts and Illness?

Growth spurts, teething, and minor illnesses are natural developmental events that can temporarily derail breastfeeding patterns. Babies may feed more frequently, become fussier at the breast, or refuse to latch altogether—leading parents to question their supply or methods. These fluctuations often resolve within days, but without proper context, they can be misinterpreted as breastfeeding problems or signs of failure. Mothers may be tempted to supplement or wean prematurely, disrupting the supply-demand cycle and triggering avoidable lactation difficulties. Proactive education on expected feeding behavior changes, along with reassurance and supportive check-ins, can help families ride out these phases with greater confidence and fewer interruptions to their breastfeeding goals.

Final Thoughts: Embracing the Journey and Redefining Expectations Around Breastfeeding

Breastfeeding is one of the most biologically natural yet socially complex acts a new mother can undertake. It is celebrated, scrutinized, stigmatized, and mythologized—all while being deeply personal. This complexity helps explain why breastfeeding is hard, not because mothers are ill-equipped or uninformed, but because the landscape they must navigate is layered with physical, emotional, cultural, and systemic challenges. From latch struggles and milk supply confusion to mental health concerns and social stigma, the barriers are numerous—but not insurmountable.

To move forward, we must first normalize the conversation around breastfeeding problems without shame or guilt. Education must be expanded to include not only the mechanics of breastfeeding but also its emotional and psychological terrain. Healthcare providers need better training, workplaces need stronger policies, and families need clearer guidance on how to support breastfeeding mothers. Breastfeeding troubleshooting should not be reserved for crisis moments but integrated into routine care from pregnancy through postpartum and beyond.

Ultimately, the decision of how, when, and whether to breastfeed should rest solely with the mother—well-informed, well-supported, and free from coercion. Empowerment, not pressure, is the cornerstone of maternal and infant health. And when we honor the full spectrum of feeding experiences, we make space for all mothers to find pride and peace in their choices. Breastfeeding will never be easy for everyone—but with empathy, education, and support, it can become less hard, more manageable, and infinitely more meaningful.

Further Reading:

Overcoming breastfeeding problems