Introduction: Why Understanding Nutrition Is Foundational to Healthy Living

In an age where food choices abound and dietary trends shift with dizzying speed, the value of understanding the nutrition definition becomes not just relevant but essential. Knowing what nutrition really means—beyond calorie counts or fad diet rules—lays the foundation for making smarter, more intentional choices about what we eat. Nutrition is not merely about eating less or following rigid plans; it’s about equipping the body with the necessary building blocks to sustain life, prevent disease, and optimize function. To truly embrace healthy eating habits, we must first demystify what we mean by “nutrition” and examine how this understanding can empower better daily decisions. This comprehensive guide will unpack the key principles of nutrition from a biological, psychological, and practical lens, offering expert insights into how knowledge translates into lifelong well-being.

Nutrition as a field intersects with biochemistry, physiology, public health, and even behavioral science. It is not merely a static definition from a textbook but a dynamic and evolving area of study. By dissecting the nutrition definition, we create space to evaluate not only what we eat but why we eat and how those choices interact with our environment, culture, and biology. As we delve into these concepts, we’ll learn to define nutrition not just in academic terms but in practical, everyday behavior that supports a healthier, more mindful lifestyle.

You may also like: 10 Essential Nutrition Rules to Follow for a Healthy Diet for Women in 20s

What Is Nutrition? Defining the Science That Fuels Life

To properly define nutrition, we must begin with its biological core. Nutrition is the scientific study of how organisms utilize food and nutrients to sustain life, grow, reproduce, and repair. It encompasses the ingestion, digestion, absorption, transport, metabolism, and excretion of food substances. At its simplest, nutrition is the interface between food and the body. It answers questions like: What happens after we eat? How do different nutrients support cellular function? And what does the body require to operate at its best?

In practical terms, the nutrition meaning extends beyond macronutrients like carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. It also includes micronutrients such as vitamins and minerals, along with hydration and fiber—all of which play critical roles in metabolic processes. Understanding this complex system underscores why nutrition cannot be distilled into calorie-counting alone. For instance, two meals with the same calorie count can have vastly different effects on your blood sugar levels, inflammation markers, and long-term health outcomes based on their nutritional composition.

Moreover, nutrition is foundational to both preventive and therapeutic health. Nutritional science plays a significant role in managing chronic diseases like diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and certain cancers. Recognizing how food acts not only as fuel but also as functional medicine brings renewed urgency to understanding the nutrition definition in depth. Ultimately, when we ask “what is nutrition,” we are really asking: What does the body need—and how can we deliver that effectively through diet?

The Evolution of the Nutrition Definition in Health Science

The term “nutrition” might seem straightforward today, but its meaning has evolved significantly over time. Historically, nutrition was simply about sustenance—ensuring that people had enough to eat. Early understandings were focused primarily on energy provision, and the discovery of vitamins in the early 20th century radically expanded the field. As scientists began to understand deficiency diseases such as scurvy or rickets, the nutrition nutrition meaning took on new significance.

By the mid-20th century, nutrition became more than survival—it became strategic. Governments developed food pyramids, daily recommended allowances, and dietary guidelines in response to widespread nutrient deficiencies and public health concerns. These frameworks helped people learn what a “balanced diet” should include, but also introduced rigid dietary rules that at times oversimplified complex biological needs.

Today, the modern nutrition definition incorporates not only biochemical components but also psychosocial, economic, and environmental factors. Nutrigenomics, for example, explores how individual genetic profiles interact with nutrients, offering personalized dietary recommendations. Similarly, food systems research investigates how agricultural practices, food distribution, and socio-economic inequality impact nutritional access. These advancements have deepened our appreciation of nutrition as a holistic, multi-disciplinary science—one that continues to evolve alongside medical, technological, and cultural developments.

Nutrition Meaning in Everyday Life: Moving Beyond Buzzwords

Understanding the nutrition meaning in an academic sense is one thing—but translating that knowledge into daily life is where the true challenge lies. In the modern food landscape, terms like “organic,” “natural,” “low-carb,” and “superfood” are used liberally, often misleading consumers into equating marketing with nutritional quality. As a result, many people feel overwhelmed or misinformed about what makes food truly nutritious.

The key to smart eating lies in context. A healthy diet for a sedentary adult differs dramatically from that of an endurance athlete. Understanding nutrition means learning to assess food based on nutrient density, portion control, and long-term health impact—not on trendiness or calorie alone. A granola bar labeled “low fat” may still contain excessive sugar and artificial additives that negatively affect blood sugar levels or gut health. Conversely, foods traditionally seen as indulgent, like avocados or full-fat yogurt, can be highly nutritious when understood within their broader biochemical role.

Moreover, nutrition in daily life includes behaviors like meal planning, emotional eating awareness, grocery budgeting, and cultural food practices. For instance, recognizing that hydration affects cognitive performance just as much as a well-balanced breakfast helps shift our perception of what it means to eat well. Nutrition education must, therefore, emphasize not just nutrient profiles but also sustainable routines, practical skills, and realistic goals. Embracing the nutrition nutrition nutrition of our lives means integrating science with mindfulness.

Decoding Macronutrients: The Building Blocks of Nutrition

To truly grasp the full scope of the nutrition definition, we must examine the fundamental components—starting with macronutrients. Carbohydrates, proteins, and fats are the primary sources of energy for the body, each serving unique physiological functions. Carbohydrates are the body’s preferred fuel source, especially for the brain and muscles. They range from simple sugars to complex starches and fibers. Understanding the glycemic index and fiber content of carbs, for instance, can profoundly influence energy regulation and satiety.

Proteins serve as the structural framework for nearly every tissue in the body, from muscles to enzymes to immune cells. Consuming adequate high-quality protein—particularly from lean meats, dairy, legumes, and whole grains—helps support muscle maintenance, hormonal balance, and tissue repair. The rise of plant-based diets has also brought attention to combining different plant proteins to ensure all essential amino acids are met.

Fats, once vilified in the low-fat craze of the 1990s, are now recognized as vital for brain health, hormone production, and vitamin absorption. Unsaturated fats from sources like olive oil, fatty fish, and nuts provide anti-inflammatory benefits, whereas trans fats and excessive saturated fats are still associated with increased cardiovascular risk. Each macronutrient carries its own complexity, but all must be considered collectively to support optimal health. Knowing how to balance them is key to applying the nutrition meaning in real life.

Understanding Micronutrients: The Unsung Heroes of Optimal Health

While macronutrients supply the bulk of our caloric intake, micronutrients—vitamins and minerals—play crucial roles in maintaining physiological harmony. These nutrients, required in minute amounts, act as coenzymes, antioxidants, and catalysts for countless metabolic processes. Iron, for instance, is essential for oxygen transport; magnesium supports muscle function and nerve conduction; and vitamin D regulates immune response and calcium absorption.

The nutrition definition is incomplete without accounting for the diversity and interdependence of micronutrients. Deficiencies in B-complex vitamins, for example, can lead to fatigue, brain fog, and compromised metabolism—symptoms often misattributed to other causes. Likewise, insufficient intake of antioxidants like vitamin C and selenium may impair the body’s ability to counteract oxidative stress, contributing to aging and disease.

Micronutrient needs vary by age, sex, health status, and lifestyle. Pregnant women require higher folic acid to prevent neural tube defects, while older adults often need more calcium and vitamin B12 due to diminished absorption. Understanding how food choices translate into micronutrient sufficiency helps prevent subtle deficiencies that may otherwise go unnoticed. Integrating whole foods—fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, and legumes—into daily meals is a practical and effective way to cover a broad spectrum of micronutritional needs. In this sense, to define nutrition properly means appreciating both the macro and micro levels of dietary input.

The Psychology of Eating: Behavioral Insights into Nutritional Choices

Nutrition is not merely about biochemistry—it is deeply tied to behavior, emotion, and cognition. The nutrition nutrition meaning includes understanding why we eat the way we do, even when we “know better.” Emotional eating, food addiction, stress-related cravings, and societal cues all influence dietary patterns. Behavioral nutrition is a growing field that explores how psychological factors like reward systems, habits, and self-control affect our food-related decisions.

Modern life presents constant food stimuli—advertisements, convenience, and social events—that override our innate hunger signals. This leads to mindless eating, overeating, or the habitual consumption of nutritionally empty foods. Understanding nutrition from a behavioral standpoint involves cultivating mindfulness, building intrinsic motivation, and setting clear, attainable goals. Techniques like intuitive eating, journaling, and structured meal plans can help restore balance and control.

Furthermore, food-related behaviors are shaped by childhood experiences, cultural values, and even socioeconomic pressures. For instance, individuals raised in food-insecure environments may develop hoarding behaviors or preference for calorie-dense meals. Addressing the nutrition definition holistically means recognizing these behavioral dynamics and designing strategies to foster positive change. Education alone is not enough—behavioral support and personalized interventions are often necessary for sustainable transformation.

Nutrition and Chronic Disease: Prevention Through Smarter Eating

Understanding the full scope of the nutrition definition also requires a deep dive into its role in chronic disease prevention. Scientific evidence consistently shows that poor dietary habits are among the leading contributors to the development of non-communicable diseases such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and certain types of cancer. On the flip side, strategic nutritional choices offer a powerful form of preventive medicine, reducing disease risk and improving quality of life.

Take, for example, cardiovascular health. Diets rich in saturated fat, sodium, and added sugars significantly increase the risk of atherosclerosis, high blood pressure, and stroke. However, adopting a Mediterranean-style diet—characterized by abundant fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and olive oil—has been associated with reduced cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. These eating patterns emphasize nutrient-dense, anti-inflammatory foods that support vascular integrity and metabolic balance, offering real-world applications of nutritional science in disease prevention.

Diabetes is another condition profoundly influenced by diet. Understanding the glycemic impact of carbohydrates, the role of dietary fiber in regulating blood sugar, and the benefits of lean proteins can help individuals prevent or manage insulin resistance. The ability to define nutrition accurately in these contexts empowers individuals and clinicians alike to craft personalized eating plans grounded in science. Preventive nutrition is not about deprivation; it’s about abundance—abundance of informed choices, of phytochemicals, and of health-enhancing behaviors rooted in knowledge.

Debunking Common Myths: Clarifying the Nutrition Nutrition Meaning

As access to information grows, so does the proliferation of nutritional myths and misinformation. Social media platforms, influencer culture, and even outdated dietary guidelines can contribute to confusion, misinterpretation, and disordered eating patterns. To truly embrace the nutrition nutrition meaning, it is essential to separate evidence-based principles from popular fiction.

One widespread myth is that eating fat makes you fat. While fats are calorie-dense, not all fats contribute to weight gain. In fact, unsaturated fats found in olive oil, avocados, nuts, and seeds support heart health, hormone regulation, and satiety. The fear of dietary fat, fueled by decades of low-fat marketing, has ironically contributed to the overconsumption of sugar and refined carbs—leading to metabolic issues far more harmful than dietary fat itself.

Another misconception is that “detox” diets and juice cleanses are necessary for health. Scientifically speaking, the body possesses highly efficient detoxification systems involving the liver, kidneys, lungs, and skin. No specific food or beverage “cleanses” the body better than these natural mechanisms. A diet rich in cruciferous vegetables, hydration, and fiber supports these organs more effectively than any commercial cleanse.

Then there’s the myth of “superfoods” being magical cures. While some foods are exceptionally nutrient-dense—like blueberries, salmon, or turmeric—placing too much emphasis on a few foods misses the larger picture. Nutrition is about the totality of the diet, not individual ingredients. Clarifying the nutrition definition through this lens means embracing a whole-diet approach rather than clinging to nutritional silver bullets.

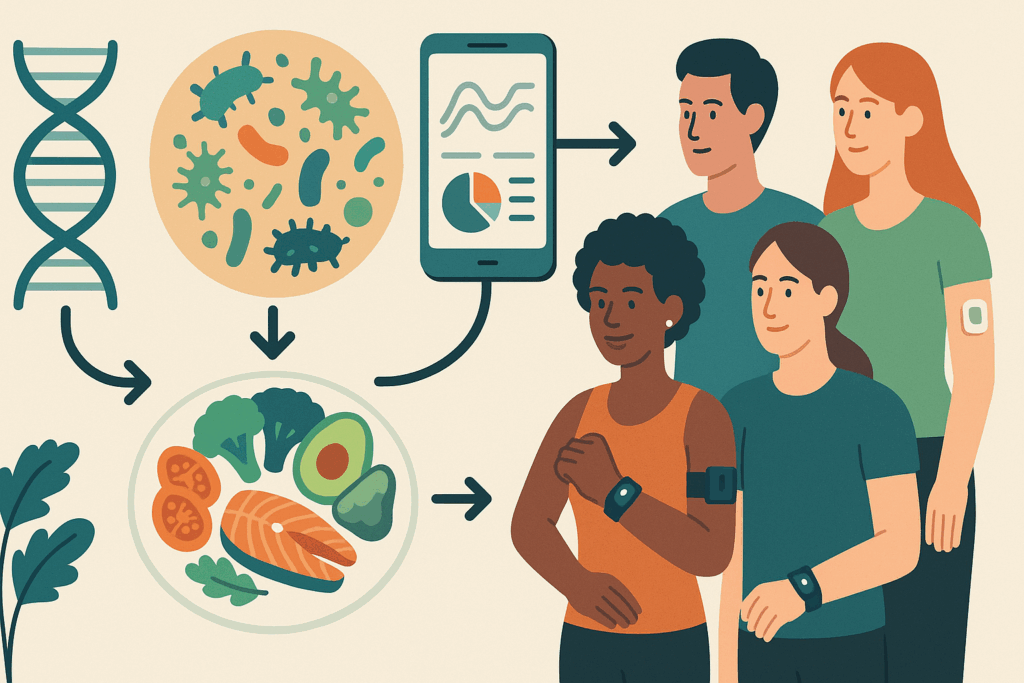

Personalized Nutrition: Bioindividuality and the Future of Eating

One of the most transformative shifts in modern nutrition science is the recognition of bioindividuality—the idea that one person’s food may be another’s poison. The rise of personalized nutrition, powered by genomics, microbiome analysis, and wearable health tech, is redefining how we apply the nutrition definition in clinical and everyday settings.

For instance, studies in nutrigenomics have shown that individuals metabolize fats, carbohydrates, and even caffeine differently based on their genetic makeup. Some people may thrive on a high-fat ketogenic diet, while others may experience adverse lipid changes. Similarly, personalized blood sugar tracking has revealed that identical meals can elicit vastly different glycemic responses in different people, depending on their gut microbiota, insulin sensitivity, and even sleep patterns.

These insights have spurred the development of apps, testing kits, and AI-driven dietary recommendations that tailor nutrition plans to individual profiles. While still an emerging field, personalized nutrition holds immense promise for chronic disease management, weight control, and even mental health optimization. To define nutrition in the 21st century is to acknowledge the nuanced interplay of genetics, environment, and lifestyle—far from the one-size-fits-all dogma of the past.

Sustainable Nutrition: Eating for Human and Planetary Health

No discussion of nutrition would be complete without considering its environmental implications. The nutrition definition has expanded beyond human biology to encompass planetary health—a recognition that our food systems must nourish both people and the planet. This holistic approach, often referred to as sustainable or planetary nutrition, is reshaping dietary guidelines across the globe.

Agricultural production accounts for a significant share of global greenhouse gas emissions, deforestation, and water use. Animal-based foods, particularly red meat and dairy, have a disproportionately high environmental footprint compared to plant-based foods. This has led to increased advocacy for diets that are not only healthful but also ecologically responsible, such as the EAT-Lancet Planetary Health Diet.

These diets prioritize whole plant foods, moderate amounts of seafood and poultry, and minimal red meat and processed items. They support biodiversity, reduce strain on natural resources, and align with evidence-based recommendations for disease prevention. For individuals, embracing sustainable nutrition might mean eating more legumes and seasonal vegetables, reducing food waste, or choosing ethically sourced products. Understanding the nutrition meaning today requires balancing personal wellness with collective ecological stewardship.

Nutrition Across the Lifespan: Adapting to Changing Needs

Nutritional needs are not static—they evolve over time, influenced by age, physiological changes, lifestyle, and health status. The nutrition definition must therefore be flexible enough to accommodate different life stages, from infancy to old age, ensuring that individuals receive appropriate support throughout their lifespan.

Infants, for instance, rely heavily on breast milk or formula to meet their nutrient needs during rapid growth and neurological development. As toddlers transition to solid foods, ensuring sufficient iron, vitamin D, and essential fatty acids becomes a priority. School-age children and adolescents require balanced diets rich in calcium, protein, and complex carbohydrates to support growth spurts, hormonal changes, and cognitive performance.

Adulthood brings its own set of challenges, including the need to balance nutrient intake with energy expenditure to prevent weight gain and chronic disease. For women, reproductive stages such as pregnancy and menopause create additional demands for specific nutrients like folic acid, iron, and calcium. Meanwhile, older adults face issues like decreased appetite, impaired nutrient absorption, and the risk of sarcopenia, necessitating focused attention on protein, B vitamins, and hydration.

Understanding the nutrition nutrition nutrition of life means being proactive, not reactive—adapting dietary strategies to anticipate and support the body’s changing requirements rather than waiting for deficiencies or illnesses to arise.

Practical Strategies for Smarter Eating Habits

Translating nutritional knowledge into daily practice remains a central challenge. While understanding the nutrition definition forms the theoretical foundation, building sustainable habits requires practical tools, environmental cues, and behavioral discipline. Fortunately, simple changes can yield significant results over time.

Meal planning is one of the most effective strategies. It reduces impulsive food choices, ensures nutrient diversity, and supports portion control. Preparing meals at home not only enhances the quality of ingredients but also reinforces mindful eating patterns. Even busy individuals can benefit from batch cooking, freezer-friendly recipes, or slow-cooker options that make healthy eating more accessible.

Grocery shopping with intention is another powerful habit. Focusing on whole foods, reading nutrition labels, and avoiding the center aisles of supermarkets—often filled with ultra-processed foods—can drastically improve dietary quality. Keeping healthy snacks like cut fruit, nuts, and yogurt on hand can help curb cravings and reduce dependence on vending machines or fast food.

Portion awareness is equally important. Using smaller plates, measuring servings, and avoiding distractions during meals can prevent overeating. Hydration should not be overlooked either; drinking water regularly supports metabolism, aids digestion, and helps distinguish true hunger from dehydration cues.

By implementing these evidence-backed strategies, individuals bring the nutrition meaning to life—not as a theoretical ideal but as a daily commitment to health and well-being.

Empowering Nutrition Literacy: From Knowledge to Action

At the heart of all dietary improvement lies nutrition literacy—the ability to understand, evaluate, and apply nutritional information. Enhancing literacy means going beyond memorizing nutrient charts; it’s about learning to question claims, interpret labels, and make choices that align with personal health goals and values. Strengthening this form of literacy enables people to move confidently from confusion to clarity.

Schools play a foundational role in developing nutrition literacy from an early age. Integrating evidence-based nutrition education into curriculums helps children understand the connection between food and health, creating lifelong habits. Similarly, public health campaigns that simplify complex information—such as plate models or portion visuals—can make a tangible difference at the population level.

On an individual level, accessing credible sources is essential. Peer-reviewed journals, registered dietitians, and accredited institutions offer far more reliable insights than unverified social media posts. Asking critical questions—What’s the source? Is this claim backed by evidence? How does this fit into my overall lifestyle?—turns passive consumers into informed participants in their own health.

Ultimately, embracing the full nutrition definition means transforming knowledge into action, values into habits, and science into sustenance. This is where change truly happens—not in the pages of textbooks, but in kitchens, grocery aisles, and lunchboxes around the world.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) on Advanced Perspectives in Human Nutrition

1. How does the nutrition definition evolve across different scientific disciplines?

The nutrition definition is not static—it shifts based on the lens through which it is studied. In biochemistry, it revolves around the molecular breakdown of nutrients and their role in cellular metabolism. Public health experts, however, may define nutrition through its impact on population health, food policy, and disease prevention strategies. Meanwhile, behavioral scientists explore how psychological, cultural, and social factors shape eating habits and nutritional outcomes. This multidimensional evolution of the nutrition definition illustrates how deeply embedded it is within both the biological and societal frameworks of human life.

2. Why does the gut microbiome significantly alter how we interpret what is nutrition?

The gut microbiome offers a transformative lens into what is nutrition by revealing that nutrient utilization is highly individualized. Each person hosts a unique composition of gut bacteria that can alter the bioavailability and metabolic effects of nutrients. For example, fiber intake may support metabolic health in one individual by promoting butyrate production, while in another, it may have minimal impact. This personalization challenges one-size-fits-all dietary guidelines and necessitates a more nuanced understanding of nutrition meaning. Incorporating microbiome profiling into nutrition assessments may eventually redefine personalized medicine and dietary interventions.

3. What are some emerging biomarkers that help us better define nutrition on a cellular level?

Biomarkers such as methylation patterns, telomere length, and nutrient-responsive gene expressions are now helping scientists define nutrition far beyond basic dietary intake. These markers provide insights into how well the body utilizes nutrients and how those nutrients impact long-term cellular health. For instance, changes in DNA methylation may indicate nutrient deficiencies or excessive oxidative stress. Additionally, real-time metabolomics is enabling the dynamic tracking of nutrient metabolism, reshaping the nutrition nutrition meaning in clinical diagnostics. This scientific evolution makes it possible to predict health trajectories through nutrient monitoring.

4. How do economic disparities influence the global nutrition nutrition nutrition narrative?

Nutrition nutrition nutrition isn’t just about food composition—it’s also about access and equity. Socioeconomic disparities strongly impact diet quality, food security, and overall nutritional health. In low-income settings, calorie-dense but nutrient-poor foods dominate, contributing to both undernutrition and obesity. Economic access also dictates exposure to nutrition education, fresh produce, and fortified foods. Thus, redefining the global nutrition meaning requires addressing food deserts, agricultural policy, and systemic inequity. Without this, the traditional nutrition definition remains an incomplete picture.

5. In what ways does artificial intelligence enhance our understanding of nutrition nutrition meaning?

AI is revolutionizing the way we interpret nutrition nutrition meaning by enabling real-time, data-driven insights from vast dietary and health datasets. It can analyze patterns in nutrient intake, genetic predispositions, and even wearable sensor data to generate tailored dietary recommendations. Additionally, machine learning models predict potential nutrient deficiencies or chronic disease risks before symptoms arise. This fusion of AI and human biology is reshaping how we define nutrition—making it more dynamic, preventive, and personalized. AI-driven nutrition apps are now integrating behavioral cues, suggesting the future of nutrition is not just about food, but about adaptive lifestyle engineering.

6. How can psychology refine our approach to what is nutrition in behavioral health?

When examining what is nutrition in behavioral health, it’s clear that food choices are not driven solely by knowledge or availability—they’re deeply tied to emotional regulation, reward circuitry, and stress response. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) now incorporates nutrition planning for patients with eating disorders, addiction, and even depression. For instance, serotonin-boosting foods may aid in managing anxiety symptoms, while glucose stability can enhance attention and reduce irritability. Thus, nutrition meaning in mental health is both biochemical and behavioral. This intersection calls for interdisciplinary approaches that blend dietetics, psychology, and neuroscience.

7. How is sustainability reshaping the nutrition definition in modern food systems?

The modern nutrition definition is increasingly tied to environmental impact and sustainable food sourcing. Nutrient density alone no longer suffices as the gold standard; now, carbon footprint, water usage, and biodiversity preservation also factor into what defines a nutritious choice. For example, plant-based proteins like lentils and peas not only meet macronutrient needs but also support ecological balance. This holistic view is critical for aligning dietary goals with climate action. In this way, nutrition nutrition nutrition embodies both personal health and planetary stewardship.

8. What role does chrononutrition play in expanding our understanding of nutrition nutrition meaning?

Chrononutrition studies how the timing of food intake affects metabolism, hormonal rhythms, and disease risk. Research shows that eating in alignment with circadian rhythms can improve insulin sensitivity, digestive efficiency, and even sleep quality. Intermittent fasting, early time-restricted feeding, and meal timing now offer evidence-backed strategies for optimizing metabolic health. These insights go beyond the static nutrition definition and bring timing to the forefront of dietary planning. The evolving nutrition meaning thus includes not just what we eat, but when we eat it.

9. How does cultural tradition expand and challenge the way we define nutrition globally?

Cultural context greatly influences how people define nutrition, often incorporating ancestral wisdom, religious practices, and local agriculture. While Western science tends to categorize foods based on macro and micronutrient profiles, traditional diets may emphasize seasonal eating, food synergies, and ritual. For example, fermented foods in Korean cuisine or the Ayurvedic concept of doshas illustrate diverse interpretations of balanced eating. These traditions may not always align with modern dietary guidelines but often achieve long-term health outcomes. Recognizing this diversity is essential to broadening the global nutrition nutrition meaning.

10. What future technologies might redefine nutrition definition in clinical practice?

Emerging technologies like smart biosensors, ingestible nutrient trackers, and real-time blood nutrient monitors are poised to completely alter the clinical nutrition definition. These innovations allow for hyper-personalized diet planning based on an individual’s live metabolic data. For instance, smart forks that monitor eating speed or glucose-monitoring contact lenses can adjust dietary recommendations on the fly. As a result, practitioners may move away from static meal plans toward dynamic nutritional algorithms. This shift will make the new nutrition meaning synonymous with responsive, precision-based care.

Conclusion: Reimagining What Is Nutrition for a Healthier Future

Revisiting the question, “what is nutrition,” we now see that it encompasses far more than food pyramids or diet trends. Nutrition is a deeply human science, one that speaks to our biology, our choices, and our communities. The nutrition definition we adopt must be holistic, inclusive, and adaptive—one that integrates macronutrients and micronutrients, genes and environment, behavior and culture. It must reflect the complexity of life itself.

Nutrition affects how we think, feel, move, and age. It impacts our resilience to disease, our energy levels, and even our emotional well-being. To embrace the true nutrition meaning is to recognize food as information, as communication with our cells, as medicine, and as a cultural expression. Understanding this equips us to make smarter, more compassionate choices—not just for ourselves, but for the ecosystems we belong to.

As we reimagine nutrition in light of new science, lived experiences, and global challenges, we must also reclaim its power as a tool for equity, sustainability, and transformation. The next time we pause to consider our meals—whether it’s a salad, smoothie, or simple home-cooked dinner—we can do so with a richer awareness of the meaning behind every bite. That is the essence of nutrition—not just as a concept, but as a call to live more consciously, more fully, and more wisely in everything we consume.

Further Reading:

Definitions of Health Terms: Nutrition